"Their service Our heritage." Quoted from the Department of Veterans' Affairs Commemorative Program.

AWM Neg. 19146

Australian Nurses POW

Captured in New Guinea

Three separate groups of Australian nurses comprise the prisoner-of-war nurses from Rabaul captured by the Japanese on the 23rd January 1942 and transported on the Naruto Maru to Japan in July 1942.

- Seven civilian nurses from Namanula Hospital, the Australian Government's Administration Hospital in Rabaul, on the island of New Britain; including one nurse, Dorothy Maye, from the Government Hospital at Kavieng, on the island of New Ireland — also attacked simultaneously by Japan.

- Six army nurses from the Australian Army Nursing Service — included as part of the 2/10th Field Ambulance detachment serving Lark Force in New Britain.

- Four civilian nurses from the Methodist Missionary Hospitals at Malabunga and Vunairima, inland from Rabaul.

Following are the nurses listed in alphabetical order and grouped according to their service.

- Administration nurses: Admin

- Alice Bowman (Bowie) Qld, Mary Goss (Mary/Goss) NSW, Grace Kruger (Grace) Qld, Dorothy Maye (Maisie) NSW, Joyce McGahan (Mac) Qld, Jean McLellan (LikLik) Qld and Joyce Oldroyd-Harris (Oldroyd) NSW

- Australian Army Nursing Service nurses: AANS

- Marjory Jean Anderson (Andy) NSW, Eileen Callaghan (Cal) SA, Mavis Cullen (Mavis) NSW, Daisy Keast (Tootie) NSW, Kay Parker (Kay) NSW and Lorna Whyte (Whytie) NSW

- Methodist Missionary nurses: MM

- Dorothy Beale Qld, Jean Christopher (Chris) NSW, Mavis Green (Mavis/Greenie) NSW and Dora Wilson NSW

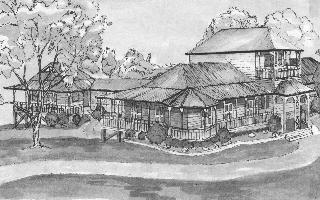

Namanula Hill Rabaul

© Graham Marriott

Traditionally, nurses are known by nicknames derived from their surnames as seen from the above: Bowie, Maisie, Mac, Whytie, Andy. And if a nickname can't be established the surname is more often used in favour of a Christian name as Oldroyd for Joyce Oldroyd-Harris. There are fundamental exceptions; Jean McLellan, Administration nurse from Namanula Hospital, was very small of stature and was named accordingly, LikLik — Pidgin for little! Pidgin English (as it was known) could not be stamped out when Australian authorities in New Guinea attempted to do so. Instead, as Pidgin, it has become an established language retaining its mix of English and German words and is now the lingua franca of New Guinea — a necessity in a country where hundreds of dialects are spoken!

With the exception of Mary Goss, all the nurses were single. Mary was married to Tom Goss, a plantation owner and a member of the New Guinea Volunteer Rifles (as were many of his civilian compatriots). Mary had been on the staff at Namanula Hospital before her marriage and subsequently was employed on a casual basis. Mary's husband, Tom, was in company with fellow plantation owners, Vic Pratt, Frank Smith and Albert Smith, as well as CJ Thompson from Carpenters Ltd. and Jack Marshall from the Rabaul Administration; this party held out in the jungle at Raniolo Plantation for six months following the Japanese invasion. Two weeks after their surrender, at the end of July, this group of six was executed by the Japanese. There is very limited information of this execution which is known to have taken place. Mary was not to know of her husband's fate until the war was over; the fate of all who perished after the fall of Rabaul was not known until the war was over.

Rabaul is seen at the northern tip of the island of New Britain.

Collectively known as the Rabaul Nurses their number increased to eighteen when Mrs Kathleen Bignell joined them in captivity. She was a civilian plantation owner who would not leave her home, in December 1941, following the order of compulsory evacuation of all women and children.

During her imprisonment years Mrs Bignell was classified as a Red Cross worker; she had been undertaking this voluntary work before her capture. She was a strong woman of singular determination; she was given the title Heroine of Rabaul in 1937 and subsequently became a recipient of the British Empire Medal. This award was granted for her gallant and tireless work during the devastating fallout, of 1937, from the eruption of Matupi Crater and the unprecedented eruption of an island, Vulcan Island, which gave birth to a new volcano, Vulcan. Rabaul is surrounded by volcanoes and stands precariously on the edge of a crater of an ancient volcano where rumblings and eruptions are frequent happenings! These two volcanoes are a constant source of disruption in that area to this day.

Mrs Bignell was at least twenty years older than the other nurses. In 1914, as Kathleen Freeman she married Charles Bignell and made her home on his plantation in the Solomon Islands. They had two daughters and one son. Mrs Bignell's daughters were in Australia when the Japanese invaded. Her son, Ted, who was twenty years old when war in Europe began, was a member of the New Guinea Volunteer Rifles and was captured by the Japanese. Sadly her daughter Jean, who had endured the loss of her first baby in Rabaul and was anxiously waiting the birth of a second child at home in Queensland when the Japanese invaded, was to lose not only her husband Dudley Roberts (one of the Administration's school-teachers) but also her brother. Both men are believed to have been on board the Japanese prison ship Montevideo Maru.

Among her many talents, Mrs Bignell was a writer of beautiful poetry, as was Grace Kruger of the Administration nurses. Some of Mrs Bignell's inspiring works on her imprisonment years — from her diary written in Japan — can be read in Yield Not to the Wind, her life story written by her older daughter, Margaret Clarence. Yield Not to the Wind has interesting chapters on Rabaul, the saga of its fall to the Japanese and the nurses' imprisonment in Japan.

Quoted from Mrs Bignell's poem, The Battle of the Hibachi, in Yield Not to the Wind are some lines about an incident which happened in Japan when the guard they called Basher more than voiced his anger after discovering how the nurses had struggled to keep warm around the cook's fire on a chilly winter's night. The nurses had no way of keeping warm and this basic comfort was forbidden by this particularly nasty guard.

- For he bared his teeth from ear to ear, and drew his sword with a terrible leer,

- He brandished it right in front of Mac's head, while his awful yells would have wakened the dead.

- Then he made a rush and a lunge at Mac, she would have been dead, if she hadn't stepped back.

- Not a sound or a move we made, no Jap will see any Aussie afraid.

- Next day Fud felt giddy and laid her head back, Basher came over and gave her a smack.

- Goss felt sick and laid on her bed, and she got a couple of beauts on her head.

- To explain, poor Bowie tried her best, and she got a bang right on the chest.

The above lines tell of that particularly frightening experience for "Mac" which is depicted in a drawing in Not Now Tomorrow. Mac is Joyce McGahan, Bowie's lifelong friend pictured (standing) with Bowie on the front cover. Until her recent passing Joyce Coutts was the sole remaining survivor of the Australian Government nurses of the Second World War who were captured by the Japanese at Rabaul. Joyce Celestine McGahan was born in Fortitude Valley, Brisbane on the 14th April 1910 and grew up on her parents Mt Sturt property on the outskirts of Warwick. Joyce was the second of three daughters born into the well-known Darling Downs family of Patrick McGahan. Her grandparents came to Australia from Ireland around the 1860s and her grandfather, Thomas McGahan, was the first Independent Member of Parliament for the Darling Downs.

Joyce trained as a nurse at Brisbane's Mater Hospital and on completion of her training took up a position as Junior Sister at Maryborough Hospital. It was a coincidence that Joyce arrived at Maryborough Hospital just as Alice Bowman left after completing her training; they were to become lifelong friends when both accepted positions on the staff of the Australian Government Hospital in Rabaul and the subsequent prisoner of war years strengthened their friendship. Within a few weeks of her return from imprisonment Joyce married Bill Coutts. Bill was a returned veteran and engaged to Joyce when he enlisted in the 2nd AIF in New Guinea in 1940. He was working for the Bulolo Gold Mining Company and Joyce met Bill at the hospital where he received medical treatment following an accident. Following their marriage, Bill returned to his job in New Guinea where they lived for some time before eventually coming back to Australia and settling in Brisbane with their two children. In Brisbane Joyce continued nursing until her 70th year; her private, retiring nature and peaceful self-assurance endeared her to all yet the shadow of the war years never left her.

Joyce and her family have made a positive contribution to Australia's heritage. Her parents and grandparents were pioneering pastoralists; her grandfather a Member of Parliament. Joyce was an Australian Government, Department of Health nurse and as such became a prisoner-of-war. Her war service was officially recognized at a Returned Services League ceremony at Greenslopes Private Hospital in April 2000. Her husband Bill, in the Second World War, served in the Middle East and New Guinea and her son served in the Vietnam War. The death of her husband and son, within a few weeks of each other in 1998, caused an enormous void in Joyce's life. Also on her birthday in 1998, Jean ("LikLik" McLellan) Harwood died in Brisbane. Then in 2000 there was the loss of Bowie; through these troubled times her daughter was a constant source of comfort. To reach the age of 99 says a lot for Joyce's strength of character and her stoic trait was evident in the last months of her decline. She died of pneumonia in Greenslopes Hospital Brisbane in September 2009.

With the screening of the telemovie Sisters of War, purportedly about the Rabaul Nurses and the Australian nuns of the Sacred Heart Catholic Mission, tribute was paid to these courageous women, yet the civilian nurses were not featured. Though not a documentary, it is the story of the fall of Rabaul with its dramatic consequences; the theme centres around a developing friendship between an army nurse and a nun and concentrates on the six Australian Army Nurses. It is said that the Australian nuns were to be sent to Japan with the nurses but the persuasiveness of the Bishop of Rabaul saw them interned with all 360 missionary people for the duration of the war. One of these Australian nuns, from memory believed to be Sr. Philomene, was entrusted with the custody of Joyce's valuable and cherished gold watch, carefully hidden in a match-box during the entire Japanese occupation. It was returned safely to Joyce, in that same match-box, after the war and is now proudly worn by her daughter.

Raising the number to nineteen, an American civilian woman joined this group in Japan - Mrs Etta Jones. Mrs Jones was a gracious American school-teacher considerably older than the Rabaul Nurses, whose ages ranged from 25 to 35. She was taken prisoner on one of the Aleutian Islands and transported to Japan after the execution of her husband, an American meteorologist — another of war's cruel tragedies resulting from the invasion of those islands by the Japanese. The life story of this Alaskan Pioneering woman, Last Letters from Attu, (published in 2009) was written by her grand-neice, Mary Breu.

Pictured, free at last, is a happy group of Rabaul Nurses recuperating in Manila; Bowie is second from the left (waving), standing with her friends from Namanula Hospital, Grace Kruger, Joyce McGahan and Jean McLellan. Grace Kruger, like Mrs Bignell, was also a writer of poetry as mentioned before. As did most of the nurses Grace stealthily kept a diary, but with one exception; the entire diary was skillfully and vividly written in rhyming verse.

- Back row from left to right:

- Grace Kruger (Admin), Alice Bowman (Admin), Joyce McGahan (Admin), Dorothy Beale (MM), Dora Wilson (MM), Joyce Oldroyd-Harris (Admin), Mary Goss (Admin), Mrs. Bignell, Mavis Cullen (AANS), Kay Parker (AANS)

- Front row from left to right:

- Jean McLellan (Admin), Jean Christopher (MM), Dorothy Maye (Admin), Mrs. Jones, Mavis Green (MM),

Lorna Whyte (AANS), Daisy Keast (AANS) - Sick in Hospital:

- Eileen Callaghan (AANS) and Marjory Jean Anderson (AANS)